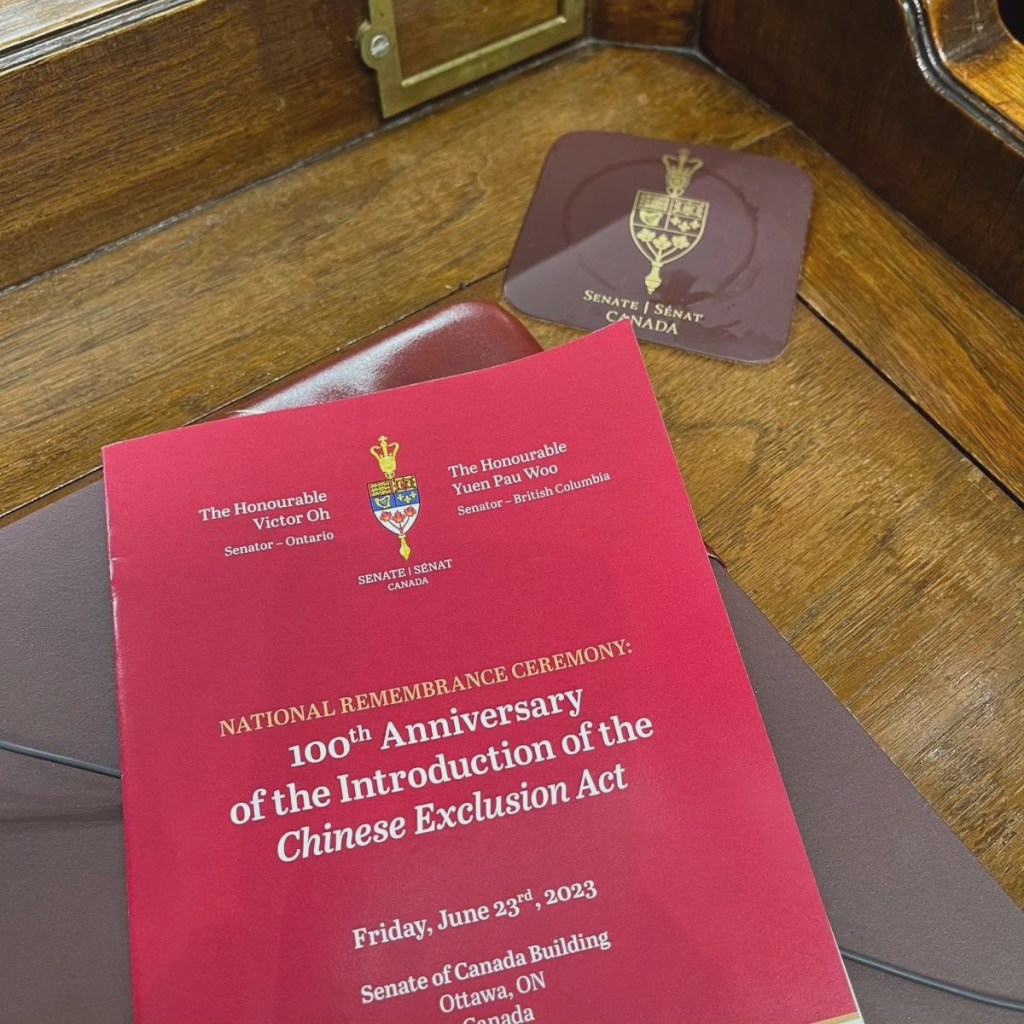

It was going to be a historical moment and the place where it was going to happen was significant. The place is a former train station that was a part of the railway network that Chinese labourers built across Canada. Currently the temporary home of the Senate of Canada, it was an appropriate venue to hold the National Remembrance Ceremony for the 100th Anniversary of the Introduction of the Chinese Exclusion Act.

The Act was officially called the Chinese Immigration Act and was passed into law on July 1st, 1923. It prohibited the Chinese from entering Canada, with a few exceptions. The date coincided with Dominion Day, now known as Canada Day. For decades, the Chinese called it Humiliation Day. When I was a kid, I never understood why my father refused to celebrate Canada’s birthday. I was an adult when I finally discovered this was the reason why. That’s why I wanted to see this ceremony; to see how far Canada has come since it enacted that racist law. The ceremony was held in the Senate on June 23, 2023, a week before the actual July 1st date.

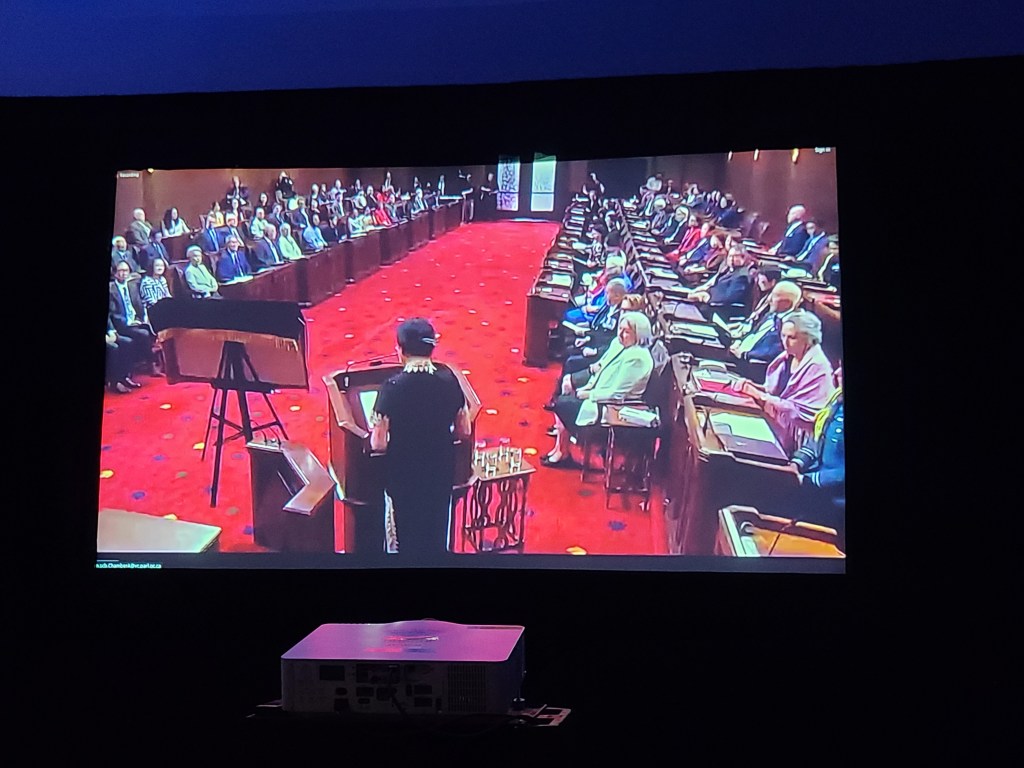

My family was directly affected by the Act that was passed by Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King’s government in 1923. The Exclusion Act forced the Chinese to register with the government or risk fines or deportation or imprisonment. My father was 13 years old when he paid $500 to enter Canada in 1921, arriving just two years before the Act was passed. It separated him from his family in China for 24 years until the law was challenged and repealed in 1947. Since I didn’t get an invitation to the ceremony, I did the next best thing. I drove to Ottawa with other members of the JIA Foundation, a non-profit organization dedicated to ensuring Montreal’s Chinatown history and stories are celebrated and not forgotten. There, I joined the Ottawa Chinese community to watch a live stream of the event at the Ottawa Convention Centre.

I wasn’t sure what to expect as I entered the ballroom in the Convention Centre that was set up to accommodate a few hundred people, but I enjoyed the three hour ceremony. After opening remarks and an Indigenous Blessing, a commemorative plaque was unveiled. It will be installed at the Chinese-Canadian Museum when it opens in Vancouver on June 30th.

Of course, there were speeches, but they included touching personal stories from Chinese Senators and Ministers about how the Exclusion Act affected their own families. And there was entertainment. Right on the floor of the Senate where the Act became law, were performances that reminded everyone of the damage and suffering it had caused. The Goh Ballet performed a dance called “Pathways to the Future”. A song that was written by an unknown composer 100 years ago in protest of the Act, entitled “Never forget July 1st” was performed by the National Remembrance Ceremony Choir, conducted by Chin Ki Yeung. The music was composed by Ashley Au. But it was Christopher Tse’s powerful spoken word performance that brought everyone in the senate to their feet. Later on, when he arrived at the Convention Centre to meet the community, I asked him what it meant for him to be able to recite his poem in the Senate.

“It’s an honour for sure. To have that space in this building, in this instance that represents a government that was responsible directly for putting this legislation in place in the first place,” said Tse. “So it feels strangely symbolic, a bit of a full circle.”

Others I spoke to felt the same way. Anto Chan, host of the live-streaming event at the Ottawa Convention Centre said that seeing the past 100 years acknowledged was powerful. Melissa Tam, whose family was also affected by the Act, felt the ceremony was important as people are still dealing with issues.

So, this Saturday, July 1st, I will celebrate Canada Day as usual. I will also wonder how my father, if he were still alive, would have felt about the Remembrance Ceremony. Thanks to him and all the ancestors who fought for the right to stay in this country, their children, grandchildren and new immigrants enjoy all the benefits of being a Canadian.

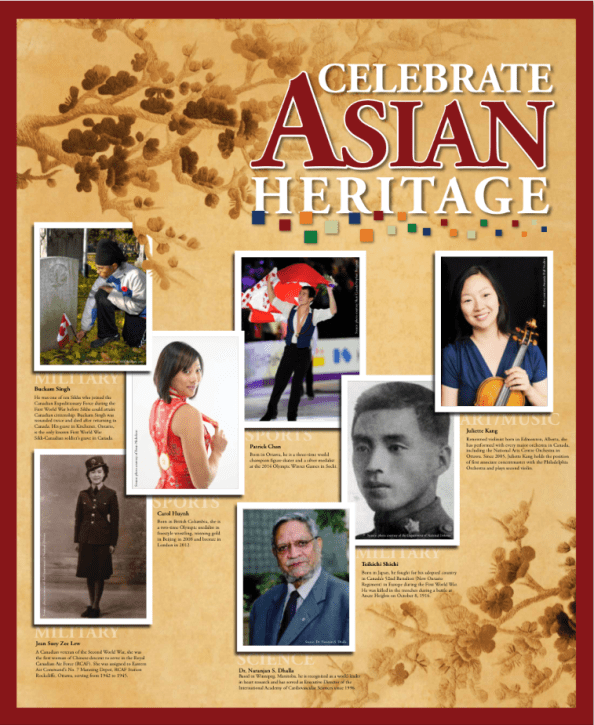

However, we still find ourselves fighting anti-Chinese sentiments in spite of all the financial, economical, and artistic contributions the Chinese have made to this country. I think part of the fight is to tell people who we are and what we bring to the table. Sharing our culture, knowledge and friendship is ongoing, but we are more than just a menu at a Chinese-Canadian restaurant. We are a part of the beating heart that drives this country forward.

We are Canadian.